empathic unsettlement in art spiegelman's maus

how a frame-story structure and anthropomorphism prevent full identification with victims of trauma

This was an essay I wrote for an English class when I was a freshmen in college around 2018-2019. I decided to cut down the title, add sections, and share it here.

Content Warning: This essay discusses and displays scenes from Maus that some may find disturbing.

Maus and empathic unsettlement

Much has been written about the Holocaust trauma representation in Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus. Hirsch coins the term “post-memory” to describe the transmission of trauma through generations, which she contends is seen in Maus through its use of photographs.

This thesis statement is proven through two parts. First, a summary of Maus is given, based on the edition published by Pantheon Books in two volumes, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale - My Father Bleeds History and Maus: A Survivor’s Tale - And Here My Troubles Began. Following the summary is a close reading of Maus to show how its frame story structure, psychic distance, and use of animals promote empathic unsettlement. Literary terms and other concepts mentioned in the discussion will be formally defined before use in analysis.

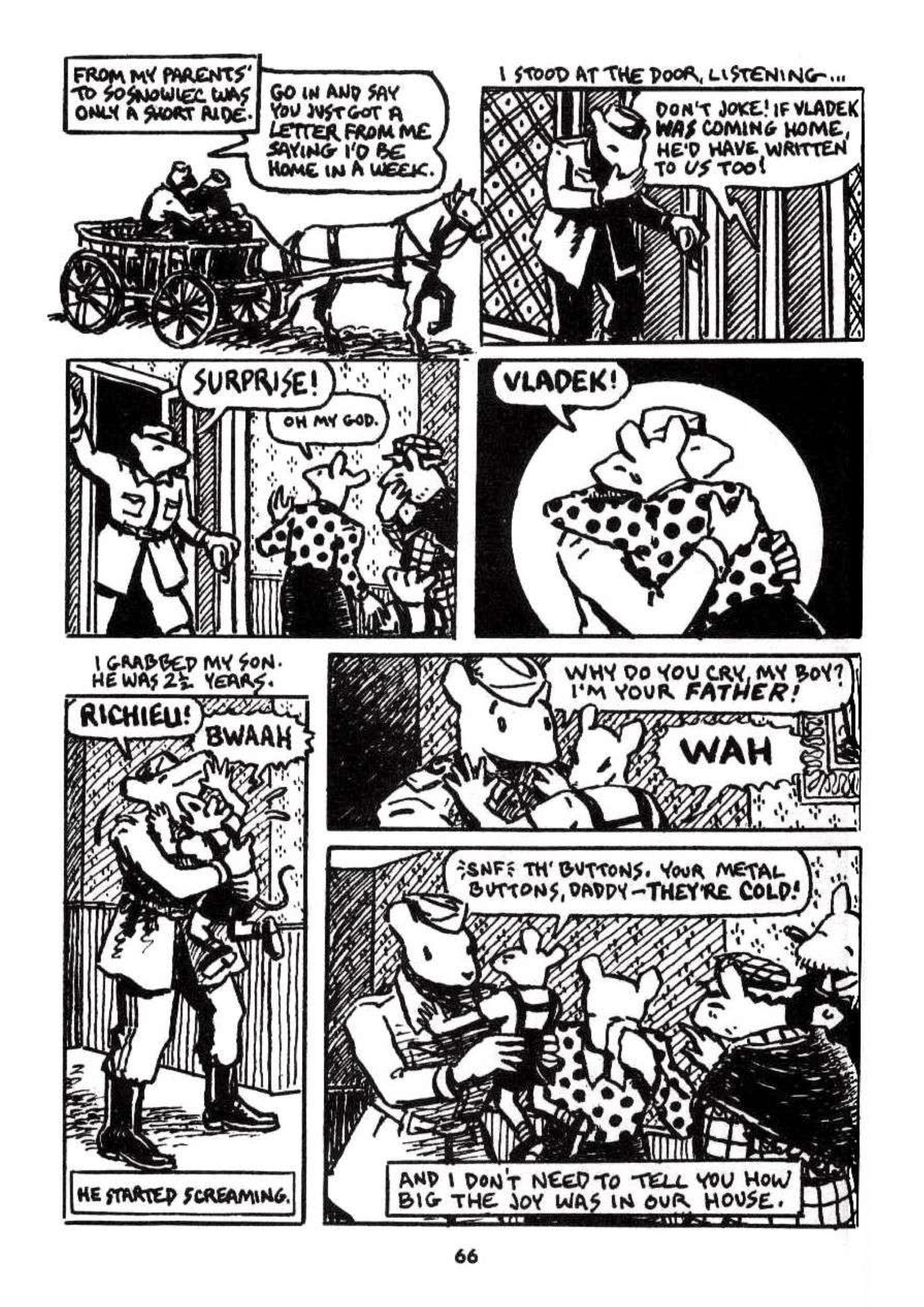

Maus follows Jewish cartoonist Art “Artie” Spiegelman as he produces a comic about how his father Vladek experienced the Holocaust. Art interviews his father over a series of visits in the 1980s to better understand the events to portray, and the setting shifts to the 1930s to 1940s whenever Vladek recounts his past. Vladek narrates how he met his wife Anja and how the two of them were displaced to the ghettos, hid from the Nazis, and were imprisoned in Auschwitz until the end of World War II. All of this is intercut with present day events such as Art taking Vladek to the hospital or the two of them walking to the bank. Eventually, Vladek passes away and the first volume of Maus becomes published. Maus ends at a time before Vladek’s death, with the Shoah survivor describing his reunion with Anja after Auschwitz to Art.

In arguing how Maus exemplifies empathic unsettlement, it is important to first formally explain the term. Aside from being a lack of full identification with victims, LaCapra writes that empathic unsettlement is a form of empathy that may result in trauma that is “secondary” or “muted.”

Frame-story structure and psychic distance

One way empathic unsettlement can be seen in Maus is through the presence of a psychic distance. Psychic distance is a term coined by Gardner to describe the distance from the text felt by the reader.

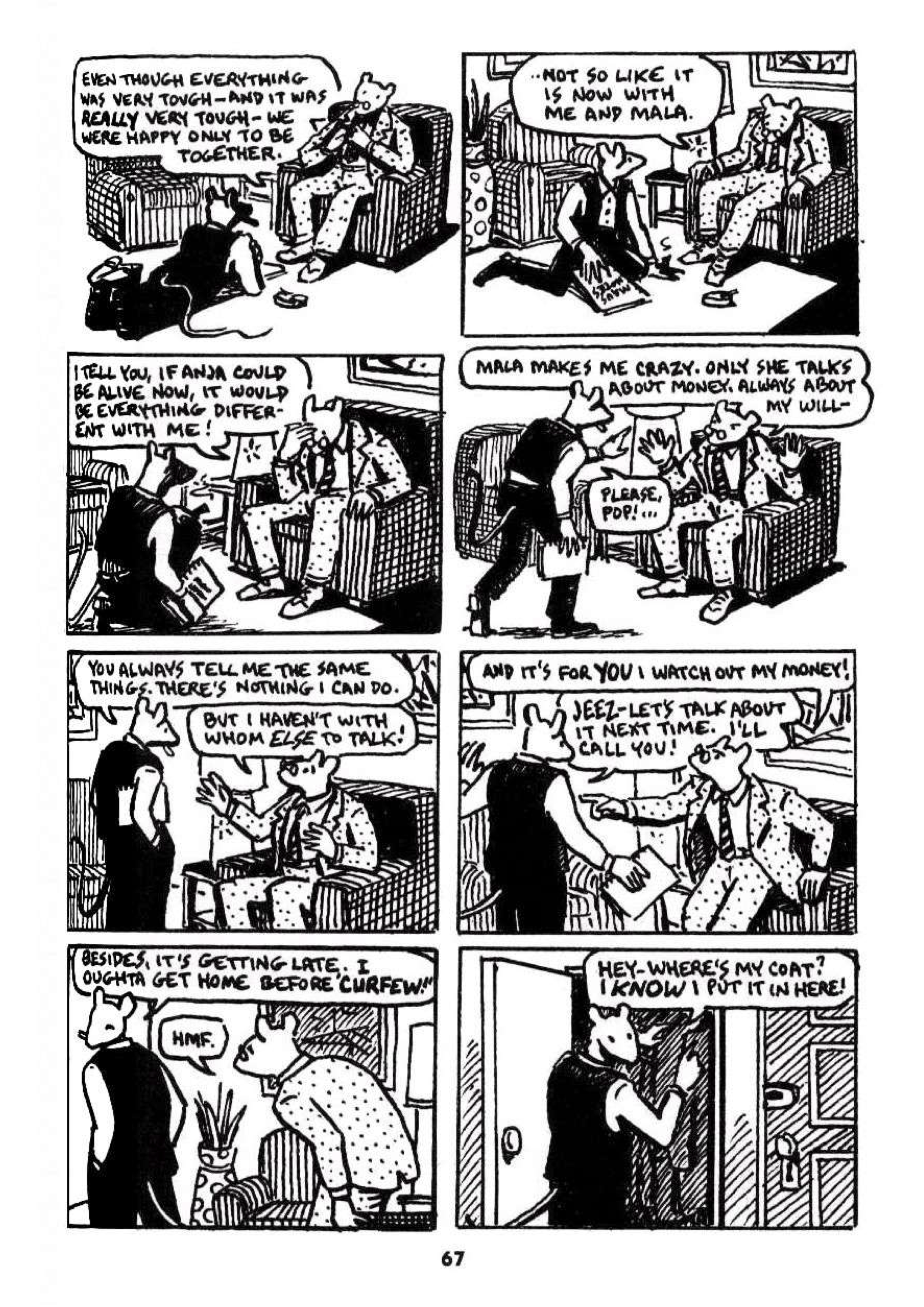

One evidence of this is how in numerous instances throughout Maus, Vladek changes the topic of the discussion to his strained marriage with his second wife Mala. Sometimes this is unintentional, such as when reminiscing about Anja, he starts comparing her to Mala.

Whether intentional or unintentional, the fact remains that Vladek’s narrative is repeatedly interrupted. This is a thought shared with Brown, who writes that Maus, being an “oral history account and also an account of oral history”, frames Vladek’s history and often disrupts it through the relationship between the interviewee and interviewer.

Contrast in anthropomorphic animals

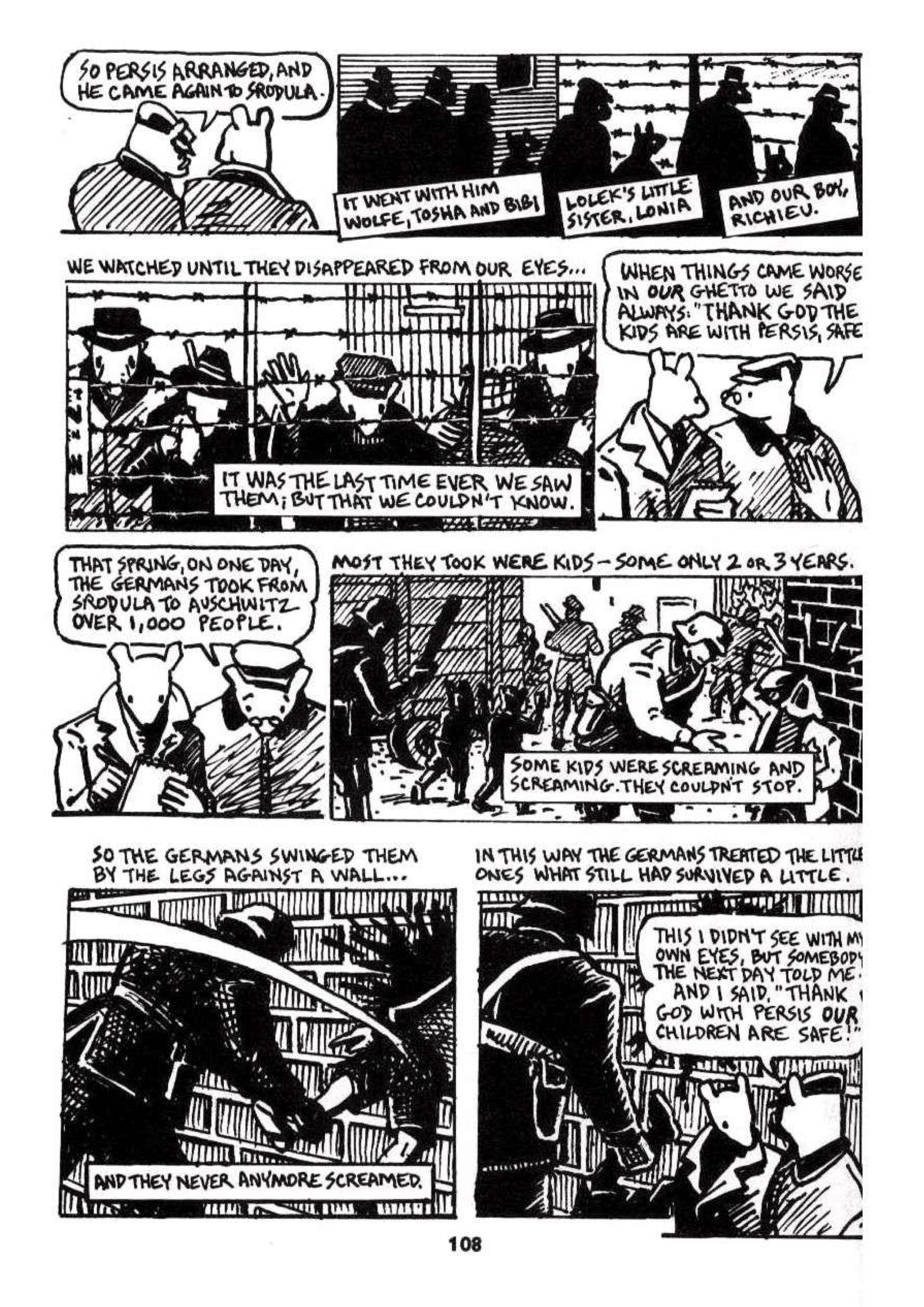

Empathic unsettlement also seems to be implied through Spiegelman’s use of anthropomorphic animals. Throughout almost the entire graphic novel, animals take the role of humans. Jews are mice, Germans are cats, Americans are dogs, the French are frogs, and so on and so forth. This paper argues that the use of animals contributes to the potential arousal of empathic unsettlement through the stark contrast between qualities associated with humanoid animals and those of the trauma represented by the book.

The anthropomorphism of animals is commonly found in children’s literature, and among Markowsky’s explanations for this are the emboldening of fantasy elements and humor.

The personal thoughts of both father and son further reflect the tragic nature of the events that the former had to endure. Although thanking God in the past that his first son Richieu did not suffer the fate of the child swung against the wall (although in reality Richieu did indeed die, albeit through poison),

The fact that both Vladek and Art allude to the intensity of the father’s psychological trauma seemingly corroborate the utter cruelty of Vladek’s experiences. The grim tone of the events Vladek underwent is evidently far different from the fantasy and humor associated with anthropomorphic animals. These lighter elements can be seen as a counterweight to the darker elements of trauma to make the horrors of Maus more removed from audiences. In writing about Maus, although not connecting it to empathic unsettlement, LaCapra has a similar idea, describing the use of animal figures as a distancing device.

Never fully identifying

In conclusion, this paper, while not assuming the reactions of readers, asserts that any empathy aroused in readers by Maus may be empathic unsettlement. It argues this through revealing how the trauma expressed by the work is secondary (due to a psychic distance resulting from its frame story structure) and muted (due to the contrasting nature of animal use in literature and the traumatic events covered in the book). The study of empathic unsettlement is significant as LaCapra believes that such a type of empathy prevents objectification of suffering while still allowing exposure to it.